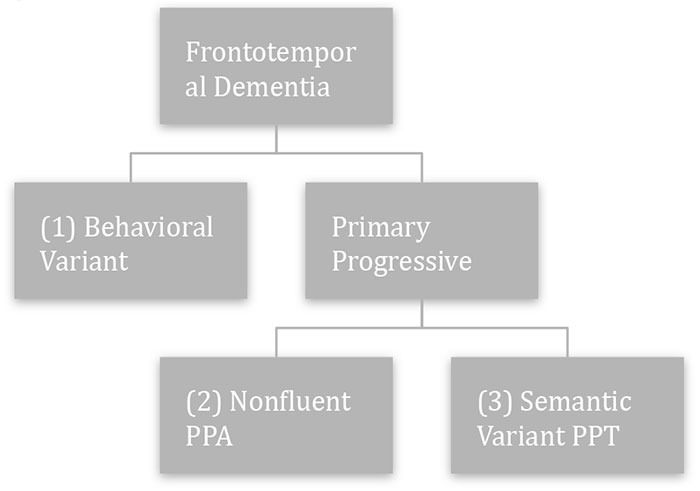

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is a heterogeneous group of dementias characterized by relatively selective and progressive atrophy involving the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain. The individual may subsequently experience changes in behavior, language dysfunction and/or motor deficits.

It is the thought to be the third leading cause of dementia (after Alzheimer’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies), accounting for approximately 10% of all dementias. Importantly, FTD is the second most common form of early-onset dementia, with approximately 70% of cases demonstrating symptoms prior to the age of 65. Symptom onset typically occurs in the sixth decade of life; however, symptoms may appear as early as one’s 30s to as late as their 90s. There is a strong genetic component to FTD, and it is inherited in approximately 1 of 3 cases.

There are three main syndromes defined by the most prominent and early features at presentation:

Behavioral Variant Frontotemporal Dementia

The most common presentation is the behavioral or frontal variant, which typically occurs between the ages of 40 and 65. It is estimated to account for 50-60% of FTD cases. Most notable is the progressive decline in one’s ability to control or alter their behavior in different social contexts. This may result in embarrassing or inappropriate social situations/interactions. The patient typically does not have insight into behavioral changes.

Signs and symptoms:

- Hyperoral behaviors (e.g., overeating, specific food restrictions, sweet cravings)

- Stereotyped and/or repetitive behaviors

- Simple and repetitive movements (e.g., tapping, clapping)

- Complex, compulsive or ritualistic behaviors (e.g., rituals, hoarding, walking fixed routes)

- Stereotypy of speech (persistent repetition of words, sayings, phrases for no apparent purpose)

- Decline in personal hygiene

- Hyperactive behavior (e.g., wandering, frustration or aggression)

- Hypersexual behavior

- Impulsive acts (e.g., shoplifting, impulsive spending)

- Apathy or inertia

- Lack of insight into the person’s own behavior develops early

- Emotional blunting (e.g., loss of empathy or sympathy, indifference toward others)

- Executive dysfunction with relatively intact memory

Semantic Variant Primary Progressive Aphasia

The semantic variant, also known as the temporal variant, is thought to account for ~20% of FTD cases. The most common problem is anomia (problem with naming). Other language abilities are generally spared early in the course of the disease. Therefore, individuals may actually be able to “talk around” the meaning of the word they cannot produce. However, the most characteristic feature is that, as the disease progresses, there is also a loss of meaning or knowledge for the words they are having difficulty producing due to a breakdown in semantic memory. Impairments can go beyond language and may therefore impact recognition of visual objects and/or familiar faces.

Signs and symptoms:

- Anomia or difficulty naming (often worse for nouns than for verbs)

- Naming errors that typically consist of substituting prototypes (e.g., dog instead of camel) or superordinates (e.g., animal instead of camel)

- Fluent speech that may be empty of meaning

- Impaired single-word comprehension

- Spelling and reading errors, particularly with irregular words

- Impaired recognition of visual objects and/or familiar faces

Nonfluent Variant Primary Progressive Aphasia

Progressive non-fluent aphasia is characterized by effortful and nonfluent speech. Nonfluent speech is the result of apraxia of speech and agrammatism.

Signs and symptoms:

- Speech sound errors resulting from speech apraxia (problems with planning/coordination of muscle groups needed for articulation): word insertions, deletions, substitutions, or alterations

- Difficulty with complex sentences; however, individuals retain ability to produce/understand simpler sentences earlier in the disease course. May see omission of smaller words (e.g. articles and adjectives)

- Apraxia of other orofacial movements and swallowing (e.g., yawning or coughing on command)

Treatment for Frontotemporal Dementias

Given the relatively earlier age of onset, there are some issues that may be particularly relevant for individuals with FTD and their families. For example,

- Families experiencing FTD may be more likely to have dependents at home

- Financial difficulties are not uncommon as the individual may be working at time of diagnosis. Thus there may be an abrupt reduction in family income.

- Decline in social functioning (as seen in the behavioral variant) can negatively impact personal relationships and be particularly challenging for family members.

Unfortunately, there are currently no therapies that alter the progression of FTD. As such, interventions are usually directed at managing current symptoms.

- For caregivers, programmed respite and/or psychological support are important.

- Options for pharmacotherapy are limited and results are often mixed. However, there is some evidence of improvement of behavioral symptoms with use of trazodone and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

- Speech and language therapy can be helpful in the case of PPA. While individuals will not have the ability to regain lost language ability, therapists can work with individuals on strategies to maximize communication (e.g., through the use of communication boards) and assess swallowing abilities, which worsen over time.

Resources

More information from The Association of Frontotemporal Degeneration